HOW IT WORKS: MICROWAVE OVENS

By: Alane Lim

Or Why You Should Always Rotate Your Leftovers

When an oven bakes you can feel the heat, and on a stovetop you can see the flames emanating from the surface. A microwave oven, on the other hand, can cook food quickly, without any visible source of heat. They work because of the type of radiation waves they’re named after: microwaves.

When you turn on a microwave oven, it generates waves of radiation which penetrate your food, zapping its water molecules and making them bristle with energy. With this added gusto, the water molecules begin moving faster and faster, knocking into each other more and more. These extra collisions translate to hotter water inside increasingly hot food.

Using the microwave also means serious competition for your oven and stove. In these conventional methods, heating starts on the surface and gradually burrows inward. But penetrating microwaves can drill right through to the center, and heat a slab of lasagna, inside and out, all at once—allowing you to heat up your food much faster.

You may have noticed that sometimes the microwave doesn’t always heat your food evenly, though. Sometimes, a slab of lasagna emerges with mystery cold spots and a center which inexplicably burns your tongue. These hot and cold spots occur because of the ways the rising and falling microwaves interact with each other.

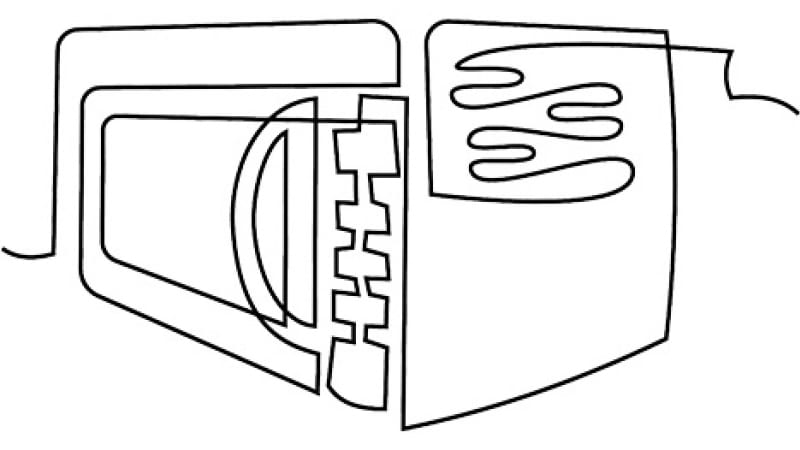

You can think of these invisible waves as squiggly lines made of interchanging upward and downward bumps, like an endless, undulating contour of equally sized camel humps. In a microwave oven, there are many such waves, all radiating from the top of the cavity and then bouncing around inside in all different directions. When two of these microwaves travel in the same direction, they can overlap. If two waves perfectly match, they combine, doubling-up in their intensity to make some spots really hot. But if all of the upward bumps in one microwave overlap with all of the downward bumps in the other microwave, they cancel each other out. With no net radiation waves to warm that spot, any portion of food sitting there stays cold.

You can see these hot and cold spots in your own microwave oven with a plate of marshmallows, as in this YouTube video.

Some of the marshmallows brown, indicating a hot spot, while others seem almost untouched by heat (most are in somewhere in the middle and kind of dimply). To combat these variations, microwaves contain rotating tables, which push all parts of the food through both the hot and cold spots. This promotes even heating.

There you have it: for best (and quickest!) reheating results, make sure your Monday night leftovers contain water molecules to energize, and that the rotating table in your microwave still works properly. (And if these criteria don’t pan out, then you still have your oven and stovetop for back-up.)