IS ORGANIC FOOD REALLY WORTH THE EXTRA COST?

By: Lisa Watson

Sales of organic products have skyrocketed in recent years, and it’s easy to see why. People associate organic food with better health, local growers, lower pesticide levels, humane treatment of animals and sounder environmental practices.

But the National Organic Program, which regulates the process of growing organic food, is actually a marketing program within the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The government stops short of making any scientific claims that organic food is safer or more nutritious than conventional foods. So with the price of food continuing to increase in recent months, shoppers are wondering if organics are really worth the extra cost.

Experts confirm that organic fruits and vegetables probably are better for the environment, and they’re often a good way of ensuring you get fresh fruit. But although a recent meta-study on organic nutrition levels showed a higher level of some vitamins, minerals and antioxidants, experts are divided on whether that translates to better health.

What makes it organic?

Farmers raise organic crops without using chemical pesticides, petroleum-based fertilizers, or sewage sludge-based fertilizers. They operate using the USDA’s list of accepted products. Organic certification is a three-year process, which requires growers to prove that the ground has not been chemically treated and all their growing practices meet organic standards.

For meat, poultry, cheese and dairy products to be considered organic, animals must be fed organic feed and given access to the outdoors. They are given no antibiotics or growth hormones. Animals produced by cloning or genetic engineering are not considered organic.

Strict rules also determine how organic food is labeled. Packaged products made with at least 95 percent organic ingredients can use the USDA organic seal. If a product is made entirely with organic materials it may also be labeled “100 percent organic.” This would include all organically grown fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as a processed food, such as cereal, whose ingredients are all organic.

If at least 70 percent of the ingredients are organic, the product can use the phrase “made with organic ingredients,” but not may not carry the USDA organic seal. If less than 70 percent of the ingredients are organic, the term “organic” may be used only to identify specific ingredients. If the only organic ingredient in a chocolate bar is milk, for example, the label cannot use the USDA seal. It can only list “organic milk” as one of the ingredients on the side panel.

Growers or sellers who intentionally mislabel products face fines of up to $11,000 for each offense. But any vendor can tell consumers their farms are in the process of becoming organic, and those claims are unregulated, according to Colleen Lammel-Harmon, spokeswoman for the Illinois Dietetic Association. This often happens at farmers markets. She says if market goers want to be sure they’re getting organics, they should ask vendors some questions to tease out whether farmers actually are involved in the process.

The Heritage Prairie Market, one of the vendors at the Green City Market, uses sustainable, organic growing methods, but has not been certified. The farm has been producing crops for less than a year, said employee Sarah Harmon. They probably will eventually get certified, but the process takes about three years and can be expensive, she said. Employees at Heritage Prairie, like those at many other organic farms, are more than willing to explain the process to interested customers.

Is it healthier?

There is much debate, even among scientists studying organic food, about whether it is actually any healthier than conventionally grown food. Many people believe that organic foods are healthier because they have higher levels of antioxidants and other nutrients, and lower levels of pesticides.

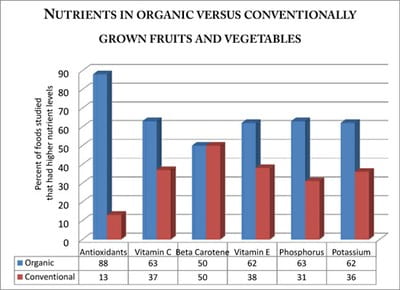

Studies show that organic fruits and vegetables are more likely to have higher levels of nutrients than their conventionally grown counterparts. Chart by Lisa Watson. Data from “New evidence confirms the nutritional superiority of plant-based organic foods,” by Charles Benbrook, et. al. The Organic Center, March 2008.

A meta-study – a scientific study that compares the results of many studies – published in March by The Organic Center, a nonprofit, showed that organic fruits and vegetables typically do have higher levels of nutrients such as vitamin C and antioxidants than conventionally grown food.

“If a person just substituted the conventional produce that they eat for organic, there would be a 25 percent increase,” said Charles Benbrook, the nonprofit’s chief scientist. “But if a person increases from three servings to six, then it will have a much bigger impact.”

Antioxidants are beneficial because they neutralize free radicals – unstable molecules that are created in the body by normal chemical reactions – by adding an electron to stabilize them, said Lammel-Harmon. Having too many free radicals is toxic, and research suggests that they are a major contributor to heart disease and cancer, she said.

But with all sorts of vitamins, minerals and other chemicals acting as antioxidants, scientists haven’t sorted out which elements are most important to cancer prevention, said Carol A. Rosenberg, MD, the director of the preventative health initiative and the Living in the Future Cancer Survivorship Program at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare. “No research shows that organic food is better in terms of cancer prevention than similar foods produced by other farming methods,” she said.

Though The Organic Center’s study has isolated various vitamins, minerals and antioxidants that organic fruits and vegetables contain in higher levels than average foods, you can’t automatically make the jump that the difference leads to higher levels of protection against cancer, Rosenberg said. “If you give individual supplements that contain a single element from a fruit or vegetable it doesn’t prevent cancer the way the studies have shown that eating a combination of foods will prevent cancer,” she said. “We don’t know the singular agent in a fruit or vegetable.”

All the elements of a diet including a variety of fruits and vegetables work in harmony to create health benefits, she said.

“We are telling pretty much everybody to eat lots of fruits and vegetables,” she said. “It’s the bastion of cancer protection.” Both organic and conventionally-grown fruits and vegetables have antioxidants, she said, and going organic may be more expensive.

Carl Winter, Ph.D., a food toxicologist at the University of California, Davis, agreed that there is not enough proof to say organics are healthier. “The burden to actually determine that is extremely high,” he said. “I’d be really surprised if at the levels we’re consuming, you’re going to be able to find a health benefit or any deleterious effects.”

Dietitians recommend at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day to get an adequate amount of antioxidants – but the more you have in your system, the better, Lammel-Harmon said. The best sources are fruits and vegetables that are rich in color. That includes blackberries, blueberries, raspberries, papaya, strawberries cantaloupe, watermelon, mangos, prunes, oranges, red grapes, cherries, sweet potatoes, spinach, broccoli, red pepper, egg plant and garlic, she said.

“I think people need to increase their fruits and vegetables, whether it’s organic or not,” Lammel-Harmon added. “That’s the bottom line.”

Why would organic foods have higher nutrient levels?

Despite disagreements over the benefits of organic foods, scientists are beginning to understand why they frequently contain more nutrients. The simplest reason is that often, organic food is produced locally and is therefore fresher. “Fresh and nutritious go hand in hand,” Lammel-Harmon said. That’s because vitamins, antioxidants and other nutrients die over time.

Local food also has a lower risk of damage and contamination during shipping, simply because it’s not traveling as far, she added. That doesn’t mean that organic food is immune from microbiological risks, however. The spinach involved in the 2006 E. coli outbreak was grown on a farm that was in the process of switching to organic. In that outbreak, at least three people were killed and 102 were hospitalized, of 199 recorded infections in 26 states, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Aside from freshness, the way that organic food is cultivated also appears to have an impact on its nutritional value, Winter said. Organic fruits and vegetables tend to grow more slowly because they do not use synthetic fertilizers. When plants are growing too quickly, they put most of their energy into getting bigger, rather than into developing a richer biochemistry, which may include antioxidants, he said.

The other positive impact is counterintuitive: Organic fruits and vegetables grow under greater conditions of stress. Since organic farmers aren’t allowed to use some of the conventional methods of fighting off disease and insects, plants have more to fight against, Winter said. With higher levels of stress, plants often produce more polyphenolic compounds, chemicals that defend plants against wounds, herbivores and stress due to photosynthesis. In humans, they act as antioxidants.

As for organic meat, national guidelines require a number of practices that are associated with more humane treatment, Benbrook said. Animals are exposed to less stress – they spend more time in the pasture and are less likely to be pushed to produce a specified amount of milk or eggs per month.

These factors contribute to healthier foods being produced by these animals, Benbrook said. Organic milk tends to have higher protein content and higher levels of heart-healthy fats such as Omega-3s, he said. Omega-3s are often associated with fish, but meat from grass-fed animals tends to have higher levels as well.

Do organics limit pesticides and environmental impact?

In addition to the extra antioxidants, many people choose organic food because chemical pesticides are prohibited in organic growing.

But even organic food has some residual pesticides, Lammel-Harmon said, because the chemicals are already in the air. “There’s nothing the farmers can do about it,” she said. That might not be a major problem, however. Current research shows that the level of pesticides associated with the food we eat is unlikely to cause harm, experts said.

“There’s no evidence that the residues of pesticides and herbicides found in foods really increase the risk of cancer,” Rosenberg said. She stressed the importance of thoroughly washing fruits and vegetables to lower the risk. “My guess is that most pesticides don’t do a lot of harm [in the amounts we consume them], but it’s inconceivable that they do nothing.”

Winter, the food toxicologist, said scientists have conducted tests that exposed animals to 10,000 times our daily exposure to pesticides, and it was an insufficient amount to cause any negative long term effects. “It’s not the presence, but it’s the amount that’s important,” he said.

Since that’s the case, the benefits of consuming lower pesticide levels in organic food alone might not be enough to justify a switch.

The risk is higher for people who work commercially with pesticides. Since they come into contact with high concentrations of pesticides on a regular basis, these people have higher rates of asthma, leukemia and certain other types of cancer than the general population, Rosenberg said.

Additionally, the lack of chemical pesticides reduces harm to the environment. “Pesticides are not completely clean in their track record,” Winter said. “You can find them in water, in soil, in places where we don’t want them.” But pesticides known to cause severe environmental problems are already restricted, even for conventional farmers.

Fertilizers allowed in organic food are typically much less potent than those that conventional farmers use, Benbrook said. They’re also more costly, so farmers are limited in the amount of fertilizer they can use. They must spend more time and effort building the innate fertility of the soil. This incidentally ties up large amounts of carbon in the organic matter, which can help combat global warming, he said.

Paying the price

Sales of organic foods reached $13.8 billion in 2005, according to the Organic Trade Association, but with the rising overall cost of food can consumers really afford to pay extra for organics?

Rosenberg likened organic food to a high-priced country club, and traditionally-grown foods to the YMCA: If you exercise at either place consistently, it’s good for your health. But only the people with the highest income levels can afford to go to the country club all the time.

“I’m being practical,” she said. “Eat as many fruits and vegetables as you can and control your weight. If you choose to go organic, don’t buy organic fruits and vegetables and then go for the cheeseburger. You still have to talk about calorie control and choosing meats versus vegetables.”

And if your budget is limited but you still like the idea of organics, Lammel-Harmon recommended choosing the organic foods that have the most nutritional impact. Fruits and vegetables with thin skin or no skin are smart buys, since they have a higher risk of cross-contamination and pesticides. That would include things like peaches and strawberries. Fruits and vegetables with a thick peel, such as avocados or bananas, have a lower risk.

She also recommended buying fruits and vegetables at the peak of the season, when they’re not only the freshest, but also the least expensive.

People start off choosing organic food to protect their family’s health, Rosenberg said. But “a growing number of people are willing to pay for organic for other reasons – to support the environmental ethic and more humane animal husbandry.”

The decision is about balancing all those concerns with the added cost. But if you keep an open mind, you will find that the cost difference isn’t always black and white. At a local Dominick’s in early June, organic baby spinach, at 79 cents per ounce, was more than twice as expensive as its non-organic counterpart, at 33 cents per ounce. Organic oranges, on the other hand, were 10 cents per pound less expensive than non-organic navel oranges, at $1.69.

“We’re fortunate in that we do have the options,” Winter said. “If people do feel very strongly about organics they have the option to purchase these things. It’s a value issue.”