THE THALIDOMIDE TRAGEDY: LESSONS FOR DRUG SAFETY AND REGULATION

By: Bara Fintel, Athena T. Samaras, Edson Carias

Many children in the 1960’s, like the kindergartner pictured above, were born with phocomelia as a side effect of the drug thalidomide, resulting in the shortening or absence of limbs. (Photo by Leonard McCombe//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

In a post-war era when sleeplessness was prevalent, thalidomide was marketed to a world hooked on tranquilizers and sleeping pills. At the time, one out of seven Americans took them regularly. The demand for sedatives was even higher in some European markets, and the presumed safety of thalidomide, the only non-barbiturate sedative known at the time, gave the drug massive appeal. Sadly, tragedy followed its release, catalyzing the beginnings of the rigorous drug approval and monitoring systems in place at the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) today.

Thalidomide first entered the German market in 1957 as an over-the-counter remedy, based on the maker’s safety claims. They advertised their product as “completely safe” for everyone, including mother and child, “even during pregnancy,” as its developers “could not find a dose high enough to kill a rat.” By 1960, thalidomide was marketed in 46 countries, with sales nearly matching those of aspirin.

Around this time, Australian obstetrician Dr. William McBride discovered that the drug also alleviated morning sickness. He started recommending this off-label use of the drug to his pregnant patients, setting a worldwide trend. Prescribing drugs for off-label purposes, or purposes other than those for which the drug was approved, is still a common practice in many countries today, including the U.S. In many cases, these off-label prescriptions are very effective, such as prescribing depression medication to treat chronic pain.

However, this practice can also lead to a more prevalent occurrence of unanticipated, and often serious, adverse drug reactions. In 1961, McBride began to associate this so-called harmless compound with severe birth defects in the babies he delivered. The drug interfered with the babies’ normal development, causing many of them to be born with phocomelia, resulting in shortened, absent, or flipper-like limbs. A German newspaper soon reported 161 babies were adversely affected by thalidomide, leading the makers of the drug—who had ignored reports of the birth defects associated with the it—to finally stop distribution within Germany. Other countries followed suit and, by March of 1962, the drug was banned in most countries where it was previously sold.

In July of 1962, president John F. Kennedy and the American press began praising their heroine, FDA inspector Frances Kelsey, who prevented the drug’s approval within the United States despite pressure from the pharmaceutical company and FDA supervisors. Kelsey felt the application for thalidomide contained incomplete and insufficient data on its safety and effectiveness. Among her concerns was the lack of data indicating whether the drug could cross the placenta, which provides nourishment to a developing fetus.

She was also concerned that there were not yet any results available from U.S. clinical trials of the drug. Even if these data where available, however, they may not have been entirely reliable. At the time, clinical trials did not require FDA approval, nor were they subject to oversight. The “clinical trials” of thalidomide involved distributing more than two and a half million tablets of thalidomide to approximately 20,000 patients across the nation—approximately 3,760 women of childbearing age, at least 207 of whom were pregnant. More than one thousand physicians participated in these trials, but few tracked their patients after dispensing the drug.

The tragedy surrounding thalidomide and Kelsey’s wise refusal to approve the drug helped motivate profound changes in the FDA. By passing the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments Act in 1962, legislators tightened restrictions surrounding the surveillance and approval process for drugs to be sold in the U.S., requiring that manufacturers prove they are both safe and effective before they are marketed. Now, drug approval can take between eight and twelve years, involving animal testing and tightly regulated human clinical trials.

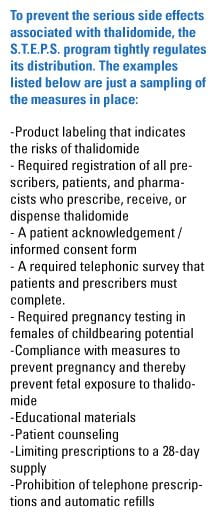

Despite its harmful side effects, thalidomide is FDA-approved for two uses today—the treatment of inflammation associated with Hansen’s disease (leprosy) and as a chemotherapeutic agent for patients with multiple myeloma, purposes for which it was originally prescribed off-label. Because of its known adverse effects on fetal development, the dispensing of thalidomide is regulated by the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (S.T.E.P.S.) program. The S.T.E.P.S. program, designed by Celgene pharmaceuticals and carried out in pharmacies where thalidomide prescriptions are filled, educates all patients who receive thalidomide about potential risks associated with the drug.

Despite its harmful side effects, thalidomide is FDA-approved for two uses today—the treatment of inflammation associated with Hansen’s disease (leprosy) and as a chemotherapeutic agent for patients with multiple myeloma, purposes for which it was originally prescribed off-label. Because of its known adverse effects on fetal development, the dispensing of thalidomide is regulated by the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (S.T.E.P.S.) program. The S.T.E.P.S. program, designed by Celgene pharmaceuticals and carried out in pharmacies where thalidomide prescriptions are filled, educates all patients who receive thalidomide about potential risks associated with the drug.

Thalidomide has also been associated with a higher occurrence blood clots and nerve and blood disorders. Northwestern University’s pharmacovigiliance team, Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR), has launched a joint project with the Walgreens pharmacy at Northwestern Memorial Hospital so that these side effects may be understood and monitored, like those affecting fetal development. RADAR, led by Dr. Charles Bennett of the Feinberg School of Medicine, combines the expertise of clinicians, academics, pharmacists, and statisticians to monitor and disseminate information about adverse drug reactions to cancer drugs.

Their project tracks the number of patients who get a blood clot after receiving thalidomide, whether or not the patient received an anticoagulant drug, which are used to help prevent clotting, and if so, which drug was used. Tracking this information will help researchers better identify the incidence and prevention of thalidomide-associated blood clots, allowing the drug to continue to serve as an effective therapy for many patients.

Pingback: Pitting Parents Against Parents • Children's Health Defense