OPTICAL ILLUSIONS AND YOUR BRAIN

By: Jennifer Cline

After striking an iceberg 375 miles south of Newfoundland, it took less than three hours for the legendary Titanic to sink 100 years ago this Sunday.

Evanston resident and Northwestern University assistant professor of cognitive psychology Steve Franconeri knows all the best optical illusions. His research focuses on visual cognition, or how the way we see affects the way we learn. He is leading a Science Cafe just for teens on Saturday, October 24, from 11:00 am—12:30 pm at Boocoo Cafe in Evanston. Science in Society asked him for a preview, and why he likes to participate in these kinds of events.

Steve Franconeri

Why do optical illusions occur?

Your eyes generate a two-dimensional photo of the world, but your brain needs a three-dimensional understanding in order for you to act in the world. Your visual system is very good at figuring out the 3D world, but it’s also doing a lot of hard work that it hides from you. Computer vision researchers have been trying to replicate this process for a long time, and they’ve learned that it’s surprisingly tough.

So do we see the world as it really exists?

You don’t see the image of the world that hits your eyes. Your brain only lets you see its interpretation of that world. This interpretation is based on your past experience.

For example, you and I are sitting across from each other. You see an image of a man who is about six feet tall sitting several feet away from you. But a man who might be 12 feet tall sitting twice as far away would generate the same image on your eye. Your brain decides that it’s a six foot tall man sitting closer to you because you probably haven’t met any 12 foot tall humans.

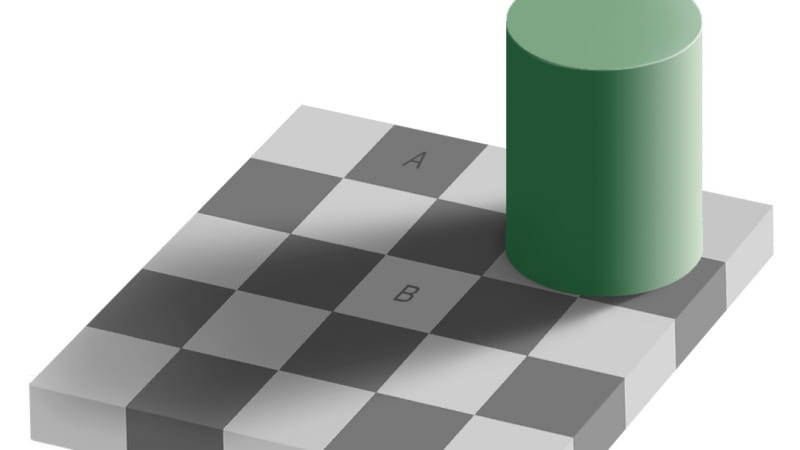

Illusions trick you by using your own experience against you. Take the checkerboard example. (At this point, Professor Franconeri pulled up the image below on his computer.)

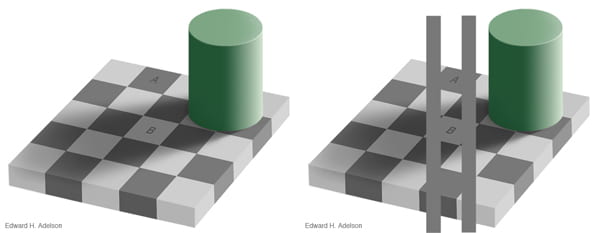

Squares A and B above are actually the same color. Don’t believe it? Check out the proof on the right. (Both images courtesy of Edward H. Adelson.)

Look at the squares marked A and B. Do they seem the same color? Of course not – B is clearly brighter. Your brain knows that the cylinder is casting a shadow over square B, and so it believes that B must be brighter. But the two squares actually are the same color. In fact, if you cover up all the other parts of the picture, and look at only the squares marked A and B, you’ll see what I mean. If you count the photons, or the basic units of light, that both squares emit you would see they are exactly the same.

Why does the brain do this with the checkerboard?

Probably because color is more important to people than how many photons something emits. Real color, and not the number of photons, tells us more about, say, if a piece of fruit is ripe or rotten.

You’ve volunteered to conduct several Science Cafes, including one on optical illusions for adults last spring. What are they like?

It’s fun. The audience really engages with this topic. We go through lots of examples of optical illusions and the attendees offer hypotheses about them. Many people have an intuitive understanding of how the visual system works, so lots of people chime in with their theories. Intuition is right about half the time, and regardless, we get to the how and why in a fun manner.

Why do you volunteer to conduct Science Cafes?

One of the things I like about Science Cafes is that I get to talk to people outside my field about my work. It challenges me to think about my work differently and express myself more clearly. It’s very healthy and helpful.

And this upcoming Science Cafe is for young people, which I’m looking forward to. I always liked science as a kid, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do when I grew up. And I had very diverse interests — I liked science, but I also liked movies and sports and art and lots of other things too. As a young person I was able to meet scientists and it helped me think about my options differently.

Pingback: Optical Illusions and Car Driving Safety US Insurance Agents